Monday, April 21, 2025

Frank James Western Outlaw

Frank James turned himself in to Missouri Governor Thomas Crittenden in 1882. He surrendered his pistol and gun belt in a quiet room at the Capitol in Jefferson City, asking only for a fair trial.

Wyatt Earp Western Lawman

If you pointed a gun at Wyatt Earp, you’d best mean business and be ready to “burn powder.” The glint in his eyes and the guns on his hips meant business.

Wild Bill Hickok Gunfighter, Lawman, and Gambler

Wild Bill and Davis Tutt squared off in the town square of Springfield, Missouri, on July 21, 1865. They stood fifteen paces apart, hands twitching at their sides. Only one man walked away.

Clay Allison Gunfighter

Clay Allison entertained himself by shooting up dance halls and small towns, making respectable gents leap around barefoot while he riddled the floor with bullets. He didn’t need much of a reason—just a little liquor and a bad mood.

Doc Holliday Gambler, Gunfighter, Lawman

When he wasn’t raising hell with a pistol, Doc Holliday spent most of his time at the tables, dealing faro or sitting in on a game, and if someone crossed him, they weren’t long for this life.

Custer's Last Stand

All two hundred and ten men in Custer’s command died in the fighting at the Little Big Horn. The Bismarck Weekly Tribune described the gruesome scene in their July 12 issue. Lieutenant Bradley told General Terry, “He had found Custer with one hundred and ninety cavalrymen. They lay as they fell, shot down from every side. General Custer shot through the head and body, seemed to have been among the last to fall.” (Century Magazine. 1890)

Lincoln & McClellan at Antietam

“After the battle of Antietam, I went up to the field to try to get him to move and came back thinking he would move at once,” Lincoln told his secretary John Hay. “But when I got home, he began to argue why he ought not to move. I peremptorily ordered him to advance. It was nineteen days before he put a man over the [Potomac] River. It was nine days longer before he got his army across.” (Elson, Henry W. The Photographic History of the Civil War. 1912)

Major Robert Anderson Surrender Fort Sumter

The War Department instructed Major Robert Anderson to prepare for battle but not assume a warlike stance. The government could not reinforce or supply the garrison without bringing the conflict to a head. Anderson was to make do with the materials and men he had. He was to walk a fine line between readiness and disaster. Not long after, the fall of Fort Sumter launched the Civil War. (Elson, Henry W. The Photographic History of the Civil War. 1912)

President James K. Polk

James K. Polk was probably the most unsociable, drab, stick-in-the-mud ever elected president. Fun was a four-letter word in his book. Sports, drinking, dancing, and anything to do with being around people didn’t make his A-list. Instead, he was short, scholarly, lived for his work, and avoided face-to-face conversations and confrontations. (Munsey’s Magazine. January 1897)

Friday, April 18, 2025

Actress Louise Barthel

Louise Barthel of Chicago’s German Comedy Opera Company (colorized photo of an image in the Greenbook Magazine, 1908)

Actress Lotta Faust Walking Dog

Actress Lotta Faust walking her dog in New York. (colorized photograph of an image in Greenbook Magazine, 1908)

Actress Grace Hazzard at Colonial Theatre

Actress Grace Hazzard leaving the stage door of the Colonial Theatre in New York (colorized photograph from an image in Greenbook Magazine, 1908)

Actor Frank Daniels

Actor Frank Daniel’s at his home in Rye, New York. (colorized photograph of an image in Greenbook Magazine, 1908).

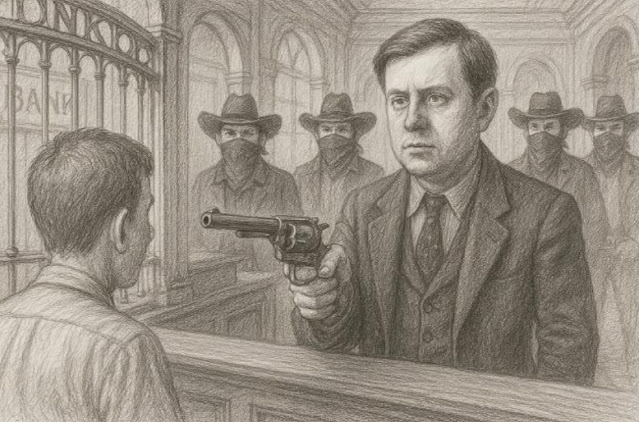

Frank James Bank Robber

Frank James turned himself in to Missouri Governor Thomas Crittenden in 1882. He surrendered his pistol and gun belt in a quiet room at the Capitol in Jefferson City, asking only for a fair trial.

Condon Bank Coffeyville, Kansas

A typical day outside the Condon Bank in Coffeyville, Kansas, until Grat Dalton, Bill Powers, and Dick Broadwell walked inside, guns in hand. Bob and Emmett Dalton entered the First National Bank across the street.

Emmett Dalton Western Outlaw

Emmett Dalton said the Coffeyville raid was a suicide mission, but “I was damned if I did, and damned if I didn’t. If I stayed out, I’d still hang. So, I rode in.”

Death of the Dalton Gang

Deputy sheriffs standing by the dead bodies of Bob and Grat Dalton. The town had done what no one else could. They’d taken down the Dalton Gang and lived to talk about it.

Black Bart California Stagecoach Robber

Black Bart was one of the most prolific stagecoach robbers to haunt the Old West, and he did it without firing a shot. He was polite, calm, and—most curious of all—he left poetry behind at the scene of his crimes.

Billy the Kid New Mexico Outlaw

Pat Garrett said Billy the Kid was always laughing—he ate and laughed, drank and laughed, fought and laughed... killed and laughed.

Pat Garrett The Man Who Killed Billy the Kid

After his election as sheriff of Lincoln County, Pat Garrett formed a posse and hunted the Kid down. Billy surrendered, was hauled to Mesilla, and convicted of killing Sheriff Brady. He was sentenced to swing on May 13, 1881.

John Wesley Hardin Western Gunfighter

John Wesley Hardin was the meanest, orneriest, deadliest cuss to sling iron in Texas. He once shot a man for snoring. That’s not a tall tale either.

Clay Allison Western Outlaw

Clay Allison entertained himself by shooting up dance halls and small towns, making respectable gents leap around barefoot while he riddled the floor with bullets. He didn’t need much of a reason—just a little liquor and a bad mood.

Lawman Bill Tilghman

Bill Tilghman was “tall and slim, straight as an arrow,” and “was not afraid of anything living.” He didn’t talk much, and the word “quit” wasn’t in his vocabulary. Once he got his man in his sights, that was the end of the story.

Thursday, April 17, 2025

Harry Tracy Oregon Outlaw

|

| Harry Tracy & David Merrill escaping from prison. |

Out in the yard, the place turned into a shooting gallery.

They gunned down the fence guard, Thurston Jones Sr. with shots to the chest

and gut. Guard Bailey Tiffany was next. He was shot dead while standing watch.

Duncan Ross hit the dirt and played dead. The escapees climbed a ladder,

dragged Tiffany with them, and used his corpse as a shield. As they hit the

tree line, Tracy put a bullet into Tiffany’s head. Three guards lay dead in

three minutes.

That night, Tracy and Merrill holed up in the woods. Around

10 p.m., they met a man named Stewart and made him strip before breaking into

his house. A few days later, they forced Mrs. H. Akers to cook them breakfast,

then looted her pantry.

On June 15, they stole a team of horses near Oregon City.

The next day, they crashed Charles Holtgrieve’s home on the Columbia River,

demanded a meal, and made five men row them across. Outside Vancouver, they

mugged a rancher named Reedy for his clothes, then disappeared for two weeks.

Monday, April 7, 2025

Arapahoe Chief White Whirlwind

Chief White Whirlwind was a leader of the Arapaho people during the 1800s.

Sunday, April 6, 2025

Japanese Geisha Girls

Cosmopolitan Magazine published this photo of Japanese Geisha Girls in an 1898 issue. (We colorized the photo)

Joshua Speed And Abraham Lincoln

You might know Joshua Speed as Abraham Lincoln’s closest friend, the guy who may (or may not) have known all of Lincoln’s secrets — including the fangy, bloody ones if you’re a fan of Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter.

Edwin H. Stanton Nearly Became A Dictator After Lincoln's Assassination

Edwin Stanton damn near staged a one-man coup after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination at Ford’s Theater.

Friday, April 4, 2025

Author Nathaniel Hawthorne

If there’s one thing Nathaniel Hawthorne understood, it was sin. Not just the kind you confess on Sundays, but the deep, gut-wrenching, life-ruining kind that haunts generations. Maybe that’s because he had his own ghosts rattling in the family closet.

Benjamin Franklin, Author, Politician, Nudist

Benjamin Franklin was a genius, a statesman, a writer, an inventor—and an absolute menace when it came to women. By the time he landed in Paris in 1776, he was 70 years old, balding, a little pudgy, and set seducing the entire city.

Sir John French British General World War I

Sir John French was Britain’s top general when World War I began. He was bold, stubborn, and loved cavalry charges. Unfortunately, cavalry was useless in a war filled with machine guns, trenches, and barbed wire.

Journalist Henri Blowitz

Journalist Henri Blowitz was a one-man leak machine with a taste for drama and cigars. He didn’t chase stories, stories found him.

Actor Lewis Waller

Horace Greeley's Presidential Campaign

Artist John La Farge

John La Farge was a legend who changed the game, and he didn’t always play nice.